“something like 82% of the audience went for HIV testing – within a week of having watched the theatre piece”

Interview with Emma Durden – Theatre & Health Consultant (11/8/2014)

VH Could you describe your work briefly…?

ED I suppose my work is predominantly summed up as ‘theatre for development;’ or it’s a bit broader – I would say ‘communication for development.’

So although most of it is theatre-based work that looks at developing communities – either through addressing health issues or through addressing other issues – other work is far more focussed on health communication, and understanding what problems there are in particular areas that prevent people from taking up messages, and therefore taking up health services.

VH And you come from a theatre background, your training is in theatre?

ED Yeah. My training is particularly in educational theatre. So although I do quite a lot of writing and directing of applied theatre work, my focus of study was very much on using theatre to educate, as opposed to learning how to act, and direct, and so on…

VH And how much of your work now would you say intersects with health and healthcare, or wellbeing?

ED I would say all of it is related to wellbeing of some sort. So if it’s not particularly health then it’s looking at gender-based violence, or xenophobia, or other social issues. So when I work for example with community-based theatre groups with Twist Projects, the main focus of my work is to help develop those groups to a point where they are sustainable as organisations on their own; but the work that they do is all very much focused on social issues.

VH Would you say that that’s a broad trend in South Africa, within community theatre?

ED For anybody who wants to sustain themselves with funding, they know that applied theatre is where the funding is; it’s not in creating theatre, but in using theatre as a vehicle to get to some other objective. So – we’re kind of actively encouraging it amongst theatre groups, [by] saying ‘if you want to survive, this is one of the things that you need to look at.’

VH D’you think that, funding aside, there’s a desire within those community groups to address social issues anyway?

ED Yeah, definitely. I did some research in 2012 … I interviewed 15 community theatre groups, and they all felt very strongly that they had a responsibility as artists … to talk about the things that others don’t talk about, in their communities.

So they are doing that work regardless. But they’re not making the connection between the health industry, or the health field, and the particular issue that they’re working with. And a lot of the time it’s quite sensationalist. So there was a project that was artistically really interesting – it was a piece called ‘The Seed’ by a theatre group from Umlazi township, south of Durban … It was on HIV, and the idea was that HIV was the seed and it grew into AIDS; it was kind of allegorical in that way. But it was very sensationalist; the guy who got HIV and passed it on was a worker, who went to town to work, and he got it from sleeping with a prostitute…

So the problem with community projects looking at those issues is that they’re really looking at stereotyped ways of, say, infection, in this example. And it doesn’t leave space for people to talk about the fact that it’s far more mundane than that, and far more ordinary, and it affects everyone. As soon as they sensationalise it, people start to stereotype types of people who get HIV, rather than types of practices.

I watch that kind of theatre coming out of communities, and I feel anxious for the messages that it contains, or that it’s passing along. So … I think there’s space for intervention, from – people like me, who are … thinking more about the consequences of sensationalising it into theatre, rather than seeing theatre as a way to interrogate those issues.

VH There’s quite an interesting parallel with a woman I met at a conference in Australia [whose] … organisation worked with the media to try and de-sensationalise representations of mental health in television [drama] and advertising … And it’s – it was exactly the same issue. Well, in a way it wasn’t quite the same issue, because I think there it was about tackling something that was being used as a dramatic device –

ED Yeah, it makes for a good story to have a madman in it.

VH Whereas it’s interesting that you’ve got – the slight contradiction of wanting to be honest about what’s happening in your community, but at the same time turning it into something that scapegoats certain members of that community, potentially, or –

ED … I think there’s a huge scope for research in that area as well. What theatre should do is allow for exploration of all of the grey areas; but what people tend to do in theatre is make it black-and-white. So that it contrasts, and it has dramatic … viability. But then the audience has no space to negotiate what it means, because they’re being told that this is what it is.

… Apart from in the design of the theatre, what a lot of the community theatre groups don’t do is facilitate discussion after theatre; so people will come and watch and go. And they know that [it has a] kind of agenda-setting function, and people will go home and talk about the play, but there’s no mediated discussion about the play, which I think is more useful.

VH So there’s no counterbalancing information being given?

ED Yeah.

VH And in your work; how much would you say is to do with, if you like, measureable health outcomes? Do you think you are – do you feel aware that you’re having an impact on individuals’ and communities’ health? I’m thinking now more specifically about the kind of work that you do with AIDS –

ED We did a project years ago in a factory – I do a lot of theatre in factories – and this particular project was the first time we actually were able to measure it. And something like 82% of the audience went for testing – HIV testing – within a week of having watched the theatre piece.

But there’s no control group to compare that to. So everyone in the plant – there were 1,200 people – everybody there at the factory saw the play, and 82% of them went and got tested in the upcoming five days.

And that’s a real measureable; but most of the time we don’t have the chance to do that, so everything’s anecdotal afterwards … Particularly with the stuff we do in factories, clients come back to us and say ‘people are still talking about it,’ or ‘… they’re still singing that song at the end of the play,’ or ‘they still refer to that character who did this or that,’ but we haven’t really been able to measure whether there’s an uptake of messages – or a reduction in injuries, or whatever the key objective is.

We could find that out, especially with the injuries – because we do a lot of the work in factories with health and safety officers, so they’ll come to us and say ‘we’ve had seven hand injuries in the last month, can you do a play on hand injuries;’ and we could go back to them and say ‘well, what are your injury rates for the next six months?’ But we don’t usually do that.

VH I suppose in a way the proof – in terms of that kind of industrial work – is in the continued employment of theatre practitioners in the field.

ED Yeah … with that theatre project that we do in factories, we have about four clients who have used us consistently for ten years. And almost every year they come back, sometimes a couple of times a year … So they obviously are convinced that it works. And I’m convinced that it works [laughs].

VH What about things like wellbeing, because this is becoming quite a big deal in the UK at the moment – I suppose an idea of moving away from health and illness and thinking more about people’s quality of life? Do you think that the work that you do has an impact on quality of life, wellbeing, resilience, capacity to cope with illness, that kind of thing?

ED Definitely the industrial theatre stuff that we do does have an impact, because we focus a lot on what they call ‘employee assistance programmes,’ so we encourage people to get counselling if they’re stressed, or we provide a list of potential coping mechanisms; … so we’ve done quite a lot of work focusing on stress. [And] other work on kind of slowing down, checking your numbers: your blood pressure, and cholesterol, and your BMI, and those sorts of things – which I think fall into that wellness category, specifically health-related wellness. But beyond that – beyond industrial work – I don’t think much of the work that I do focuses on that.

Although having said that, last year I worked on a campaign particularly for women, and a big focus of the campaign was on self-esteem, and knowing yourself, understanding your boundaries, understanding how to communicate in relationships; and I think … that had a real impact on women that we did workshops with, and they loved that campaign, because it was very much about being a woman, and understanding yourself, before starting to look at health-related issues. So it was essentially a sexual and reproductive health campaign, but the getting-in was ‘who are you, and how do you define yourself?’ And people don’t get the chance to explore that very often, and I think that they really appreciated the space to do that in the workshop that we did. So that Zazi Campaign runs in partnership with the Department of Health and JHHESA [Johns Hopkins Health and Education South Africa]. Zazi, which means ‘know yourself,’ or ‘to know.’

VH And what about research? Your academic links are pretty strong, but what relationship would you say that your work has with research, and how do you present your work in a research context?

ED Some of it is based particularly on recent research in the area. So … because I supervise students, and I have links with the university, I do read recent stuff and I think this gets assimilated into what I’m writing for theatre or what I’m talking about when I’m working with theatre groups, although it’s not particularly researched in that context, but is more general … That kind of baseline research, or prior research – we don’t do that directly, we just pick up on what’s been done around the area (the area not geographically, but the field of discussion). And then research into impact or whatever – we’ve done very little of that.

VH But you do use theatre as a research tool – which is interesting.

ED Yes, in an un-formalised way. So when you do what they call ‘process theatre,’ which takes people through a process of creating a play, then that would be seen as theatre for research – or theatre as research, because then, in the process of creating the play, you are seeing how people respond to or frame a particular problem. And I don’t do very much of that process theatre, or that participatory creation of theatre. I have done in the past, so my PhD is a lot more on that, but recently I haven’t done much of that work.

VH And … the MAs [you supervise], for example, they’re theatre students … ?

ED They are in the Centre for Communication in Media and Society [at the University of KwaZulu Natal], so they’re more about communication and development studies, and less about theatre. But … their undergrad degrees or their honours degrees would be in theatre; and the work that they do most days is theatre: participatory theatre, and role-play-related work.

VH And they use those techniques to gather information about a particular topic, which is often health-related or social development-related?

ED Yeah. So they’ll do role plays on – negotiating condom use; and the result of that role play would inform how they know young men are thinking about condom use. But it’s not really well documented, so that work is often done far more as an intervention than as research. So there’s a lot of space for research in those areas, I think, too.

VH I find it interesting that you’ve got theatre undergrads going into social research … and using their theatre techniques. So rather than a social scientist bringing in a theatre practitioner, you’ve got theatre practitioners working as social scientists.

ED Yeah. I think that’s definitely the trend, far more – that it’s the people with the skills who are applying them in a particular context, rather than the people from the context coming out and trying to find the skills.

VH … I’m not sure but I would say it tends to be the other way around in the UK. Or at least that the concept of using a theatre practitioner or an artist as a social scientist is not particularly popular, or well-developed. There’s much more of a sense of people working in silos in that way.

ED Quite often we have to fight for recognition in the field. So I know it happens quite a lot with the medical field – that they don’t see this kind of social science as valid enough research to make any impact on what they’re saying about HIV, or whatever the issue is. Yeah, so I suppose there have been times when it’s been more difficult to negotiate that; but I think now everyone’s kind of fairly clear that this is how it works; these are the people who have the expertise in this area. I think also a lot of the work is very much about the interventions and who can access those communities; and theatre groups or theatre practitioners can access those communities far more easily than just pure researchers can.

VH That’s interesting – because they already have a relationship there? Or because theatre is a more accepted –

ED Yeah, a more popular tool, or a popular pastime.

VH Related to that – do you feel like some of the work you do is having an impact on policy in any way? Either locally or nationally, d’you think it’s getting to the right people?

ED I think that … particularly with work that’s funded through JHHESA and PEPFAR and UNAIDS, that kind of thing – because they have a very close relationship with the Department of Health, when we do work in that field, the Department of Health takes notice.

So for example last year I did quite a bit of work with a large group of people with different disabilities, on sexual and reproductive health. The Department of Health has a Disability Unit, which is supposed to consider how disabled people can access health services, or how health services can accommodate people with disability. But they hadn’t considered a whole lot of stuff, and so some reports that I wrote last year based on a day’s workshop, including role plays and drawing posters and things, was really leapt on by the Department of Health; and then they were very happy to come on board as a co-sponsor of pamphlets – braille pamphlets particularly for blind people, and – and just looking at … alternative ways of communicating. … Quite a lot of suggestions, as well, in terms of how health workers are working with people with disabilities. I don’t know if those have been taken up, but they’ve certainly all been sent to the Department of Health and read by them. So I think, depending on who’s funding the project and what their relationship is with the Department of Health, that’s what impacts on whether or not it’s going to influence policy.

VH And from another angle: arts practice. How do you feel you sit within, or you sit against the mainstream of arts practice in this area?

ED I would say that ten years ago people would consider you outside the arts field if this was the work that you were doing. But I think there is a greater recognition that this is theatre, and this is art … it’s just different from what they’re doing.

… I don’t think people who don’t do this kind of work know how to value it … they don’t know the impact that it has, but they do think that it is slightly less artistic, or that you’re not quite a proper artist if this is the work that you’re doing.

VH You think that’s still the case?

ED I do, but it’s amongst a smaller group of people, because the theatre community in particular is just getting smaller and smaller; and more people are realising that you have to do this kind of work to survive in this field. That’s not why I do it; I do it because this is the work that I like to do, and I would rather do than plays in theatres. But yeah, I think there’s a recognition that this is a way for people in theatre to survive, and that’s not the recognition that we want. We want the recognition that this is a valid artform, although slightly different from theatre ‘at the Playhouse.’

VH At the talk you gave the other day you were making some really interesting distinctions between community theatre, applied theatre, and – I don’t know what you’d call it – ‘High theatre,’ I suppose –

ED I think I called it ‘professional theatre;’ I was thinking of originally calling it ‘artistic theatre,’ but really there’s as much artistry in applied theatre and in community theatre as there is in that. So … the art of professional theatre is what slightly distinguishes it, the purpose of applied theatre is what slightly distinguishes that, and then the community of community theatre – so the recognition between audience and performer – is what differentiates that from the other two. But there are … so many crossovers, and – they’re become less distinctive, I think; as artforms, they’re becoming less distinctive; and it’s a case of geography, really. Geography and the funders at the bottom of the programme notes, or on the banner that’s outside the clinic.

VH There was an interesting point about community theatre and how you could have a community theatre production in the same space as a ‘professional’ production and the only difference really would be that the community theatre wouldn’t be able to charge as much of an entry fee.

ED Yeah … that is really the only difference. And I suppose it’s how people see themselves – how the people who are involved in those projects see themselves. So the community theatre groups will … say ‘we are artists, and we are a theatre group.’ And it’s only when they have greater exposure to ‘professional’ theatre that they then start to say ‘oh, well we’re a community theatre group.’

VH That’s interesting.

ED Yeah, it is. It’s a funny thing because you don’t want people to stop thinking of themselves as artists, because I think it’s a valuable thing for them to feel that they are artists. But unfortunately community theatre is seen as lesser than by people who go to the theatre.

It’s interesting. When you look at the National Arts Festival programme – when you apply … you have to note yourself either as a professional production company or a community production company. And I know people who … say ‘we must go and see some community theatre.’ So they choose what to go on the basis of ‘is it community theatre, or is it professional theatre?’ rather than what the content of the theatre is.

VH It makes it seem a very arbitrary division. I had a – related conversation when I was working with a group of ‘outsider’ artists, who were mostly people who had long-term mental health issues, but they were artists, primarily, in the context of the organisation that I was working for. And we had a conversation about the business of being an ‘outsider’ and how they defined that. And one of them said ‘I’m never going to get into the Tate,’ and I thought ‘well yes, but that doesn’t make you an outsider,’ that’s 99.9% of all artists in the world, ever! So your access to those sort of ‘higher’ bits of the mainstream doesn’t really determine whether or not you’re an outsider or an insider.

ED … if that’s set as the benchmark, if the Tate is the benchmark, is that what they aspire to? Because you know here if you ask a lot of community theatre artists ‘what do you really want to do?’ they want to go on an international tour. So Mbongeni Ngema was really responsible for finding people from communities who had talent and no training, and then putting them in a big production that went around the world. And … that’s what a lot of young community theatre artists aspire to. So while they say that … they’ve got important messages for their community, and they have a responsibility, they also would really just love to go and sing in ‘The Lion King’ in Tokyo for two years.

VH Yeah. But I think that’s probably common to most young performers – I think it’s slightly different with visual art. I mean you’d have the same with a group of musicians – if you talk to a bunch of 20 year-olds in a band, anywhere, they’re gonna want to go on a world tour …

ED Yeah, and headline at Glastonbury –

VH Exactly …

I’ve got two more questions: one is about funding – because this is the kind of eternal panic that anybody working in arts in health is in: do you feel that the work that you do in a South African context is sustainable financially? You said before that … people are choosing to do this work because it is the financially stable end of the spectrum, but do you think that your organisation and the work you do can be funded, can you imagine it carrying on in perpetuity?

ED You know, I hate funding. I feel that it’s – I feel that it creates a sense of panic and dependency in organisations that shouldn’t be there. And I wish that there were other models that we could look at.

The work that I do with the PST project, which is all the industrial theatre work, is paid for – it’s a product that is paid for by a factory; … it’s supply and demand, and it’s ordinary economics, and it is completely sustainable. And I feel that that should happen in all of the health spheres. So I feel that somebody – the Department of Health, or whoever it is – should say ‘we need people to know about diabetes, and we therefore need to buy a diabetes play.’ But given the government’s propensity to spend money on other things, I can’t see that happening.

I really struggle with funding, so I don’t really know how to answer that, because more and more … funding from outside South Africa is drying up, because people don’t really see South Africa as a priority country any more; it’s no longer a developing country … – or it’s no longer an underdeveloped country. So it doesn’t classify for all sorts of foreign funding any more.

[And] arts funding is so small, that it is less used on this kind of work, and so the funding that is accessed is health funding or social development funding.

I was talking to somebody who runs a project in Kenya; … what they do is that they sell carbon credits … it’s a water project; … they supply a person in a village with chlorine in a bottle; and you squirt a squirt of chlorine into your bucket of water collected from the river or the well … and then it makes that water safe to drink. And because the product saves so much on shipping in water, or bottling water … they mass up carbon credits, and then big multinationals, who need to buy carbon credits because they’ve just used 40 million carbon credits to build a factory, can offset their costs. So it’s this whole alternative economy… And they’re just starting a new one on social development credits …

VH So sort of corporate social responsibility stuff?

ED It is, but it’s beyond corporates that are doing it – it’s governments and it’s all sorts of things. … I think she called it ‘social cohesion credits.’ So if you … do something that causes social cohesion, or brings people together, and helps people solve problems, then you get social cohesion credits. And that’s where we would really be able to tap into that kind of trading. So it’s international trading – it’s like a Stock Market in carbon credits, and now [a] … Stock Market in social cohesion credits.

VH That’s totally fascinating.

ED Yeah … because I think it could really revolutionise the way that these kinds of projects are funded. Because it then doesn’t become just about CSI [Corporate Social Investment] funding; it actually is a need on the part of those companies … So that’s what I wish we could get more towards, this kind of trading, rather than – asking for funding, asking for money.

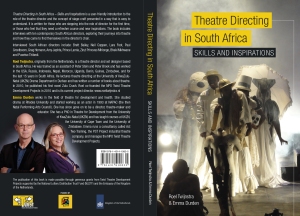

Emma’s new book, co-written with Roel Twijnstra: Theatre Directing in South Africa: Skills and Inspirations, is available by emailing info@twistprojects.co.za.